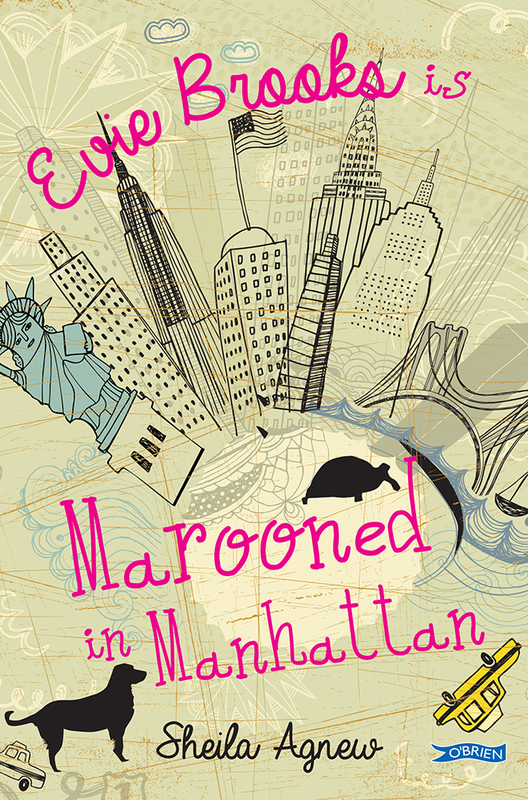

Evie Brooks is Coming to America!

May 22, 2015

The first two books in my Evie Brooks series for children will be published in the U.S. and Canada in November, 2015. Thank you to the wonderful Pajama Press and to my Irish publishers, The O’Brien Press.

It’s very much a case of fiction imitating life imitating fiction. My mother, Nora Brooks (as she was then called), moved from Ireland to New York when she was not much older than Evie. In the first book, Marooned in Manhattan, Evie moves from Dublin to New York. I moved from New York to Dublin as a child and then back to New York as an adult. Now the books are making the journey from Ireland to America.

How do I feel about that? That’s an easy one – I’m THRILLED. I suspect that it’s thrilling for most authors when their books execute that tricky transatlantic leap. But since I’m based on the U.S. side of the water, it might be even more of a head-rush for me. I’m delighted that American children will get the chance to get acquainted with Evie. And I look forward to meeting lots of them. I love the idea that the voice of an Irish child immigrant will join the canon of American children’s books. And I was definitely getting a bit fed-up with people drifting away when I said that the Evie books were only published in Britain and Ireland. Sometimes they reacted as if I’d announced that my books were published exclusively on dwarf planet Pluto. I felt like an undocumented author hitching a ride on the roof of a slow-moving train. Now I feel like Evie has been awarded a Green Card, a shot at the American dream.

If you read my last blog, you will know that I headed off to Cabarete in the Dominican Republic on a solo writing retreat for the month of April. But I didn’t write a tap on my first day. And I didn’t write on the second day either, not even a cover page, ‘Work in Progress – a novel by Sheila Agnew,’ which was a little peculiar because that’s always been my favourite part. On the third day, I got up and plugged in my laptop before heading off on the back of a moped taxi to the regular surfing beach a few miles away. Mid-morning while I was floundering around in the white-water, terrified of getting whacked in the head by my own rented surfboard, I noticed a very tall tranny dressed in fishnets and a frilly dress meandering up the almost deserted beach. I welcomed the distraction . . . . . until she ran off with my stuff. There wasn’t much I could do from that far out in the ocean except yell in rather formal textbook Spanish: ‘Ladron! Ladron!’ (Thief! Thief!). It’s mystifying as to how I could instantly recall that word but be completely unable to dredge up the simple Spanish for “stop.”

The tranny made off with my bag containing my very cheap watch, a little money, my clothes, and the novel, “The Power and the Glory” by Graham Greene. I admired her literary taste (she sensibly discarded “Writers on Writing” further up the beach). I had to walk back, scantily clad, swearing to myself. And during the course of my walk I noticed a sign that I would never have seen if I’d been praying with my eyes closed on the back of a speeding motorbike. The sign was for “The Dream Project.” Intrigued, I followed the sign in cyberspace that evening. The Dream Project is a wonderful education charity.

What began as my offer to do an author visit to the children led to me working every morning as a volunteer English teacher in A Ganar, a program which trains impoverished Dominicans between the ages of 17 and 24 to work in the local tourism industry. Teaching hadn’t been part of my plan. I had come to the DR to write, but in life, as in writing, I believe you should go with the flow when you can. I fell in love with my students and I loved teaching. And I got the opportunity to get to know the country and its people much better than the casual visitor.

The DR is located, along with Haiti, on the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean. A two-nation island isn’t a difficult concept for an Irish person to grasp but the differences between the DR (which lies on the eastern part of the island) and Haiti, to the west, seem so much vaster than the divisions between southern and northern Ireland. The Haitians have their roots in Africa while the majority of Dominicans have mixed roots. They are separated by the powerful barrier of language - the Dominicans speak Spanish while the Haitians speak French/Creole. In the thirty-year span of the worst of the Irish Troubles, approximately 3,600 people lost their lives. On this island, in a frenzied five days in October, 1937, an estimated up-to 30,000 Haitians were murdered at the behest of Rafael Trujillo, the U.S. backed Dominican dictator. The motivation behind the genocide was economic – and racial. Trujillo was obsessed with keeping out black blood. The massacre might be an example of the most extreme manifestation of self-loathing since Trujillo’s maternal grandmother was black, a fact he spent his life trying to conceal. Trujillo’s legacy lives on in a myriad of disturbing ways in present-day DR.

One intensely hot morning, I fell into conversation in the back of a bus, with a volunteer teacher, a young Dominican-American woman. She asked me what I did and I said that I was a writer.

“I have an idea for a children’s book,” she responded (a very common reaction to the news that you are a writer).

“Tell me about it,” I said.

And she proceeded to tell me her idea for a story about a young girl and a playground. Her story sounded very familiar because it has been written many times before. It was universal, it could be set anywhere; it could be written by anyone. There was no voice.

Not wishing to discourage her but not wanting to lie either, I rather cowardly changed the topic by complimenting her hair.

She smiled, trailing her fingers through her Afro, and then she grimaced:

In the DR it’s very important to a lot of people to look Spanish, to be descended from Spanish blood, to completely deny any black blood. The supermarkets are packed with expensive chemical treatments for skin whitening and hair straightening. When I was growing up, I went through such torture, such a hard time from my family, all the endless chemical treatments to straighten my hair that went on from when I was just a toddler, all that wasted time to try and make me look European.

She grinned at me – a big, infectious, life-affirming grin, the kind that makes you want to grin back. She continued:

Well, just look at me! At my face! At my hair! I have African blood. I am who I am. Now I don’t straighten my hair anymore even though my family still nag me and go crazy about it. I wear a t-shirt that says: “Proud to have a ‘fro.” And I have this niece, she’s six, she is an amazing kid. And she’s the only one in the family who looks like me. And I don’t want her to go through what I went through. I want her hair to be left natural. I want her to like herself the way she is.

She trailed off and there was a moment of silence.

“There you go,” I said. “There’s your story. That’s the story you should write.”

“You think?” she asked in a doubtful voice.

“Yes!” I said.

I don’t know if she will write it. I hope so. I hope she adds another immigrant voice to American children’s literature. It’s much more interesting and entertaining when the voices don’t all sound the same, and much more reflective of the real America. Oh, I have to go. I am in Munich visiting my twin sister who is expecting her third child. Her two boys are calling to me to read to them. They will hand me a children’s book in German and since my German is limited to “auf weidersen” pet, I will only pretend to read it. I will make up the story as I go along in my own voice. Because that’s what writers do.